Sign up for our monthly Leap Update newsletter and announcements from the Leap Ambassadors Community:

By clicking "Stay Connected" you agree to the Privacy Policy

By clicking "Stay Connected" you agree to the Privacy Policy

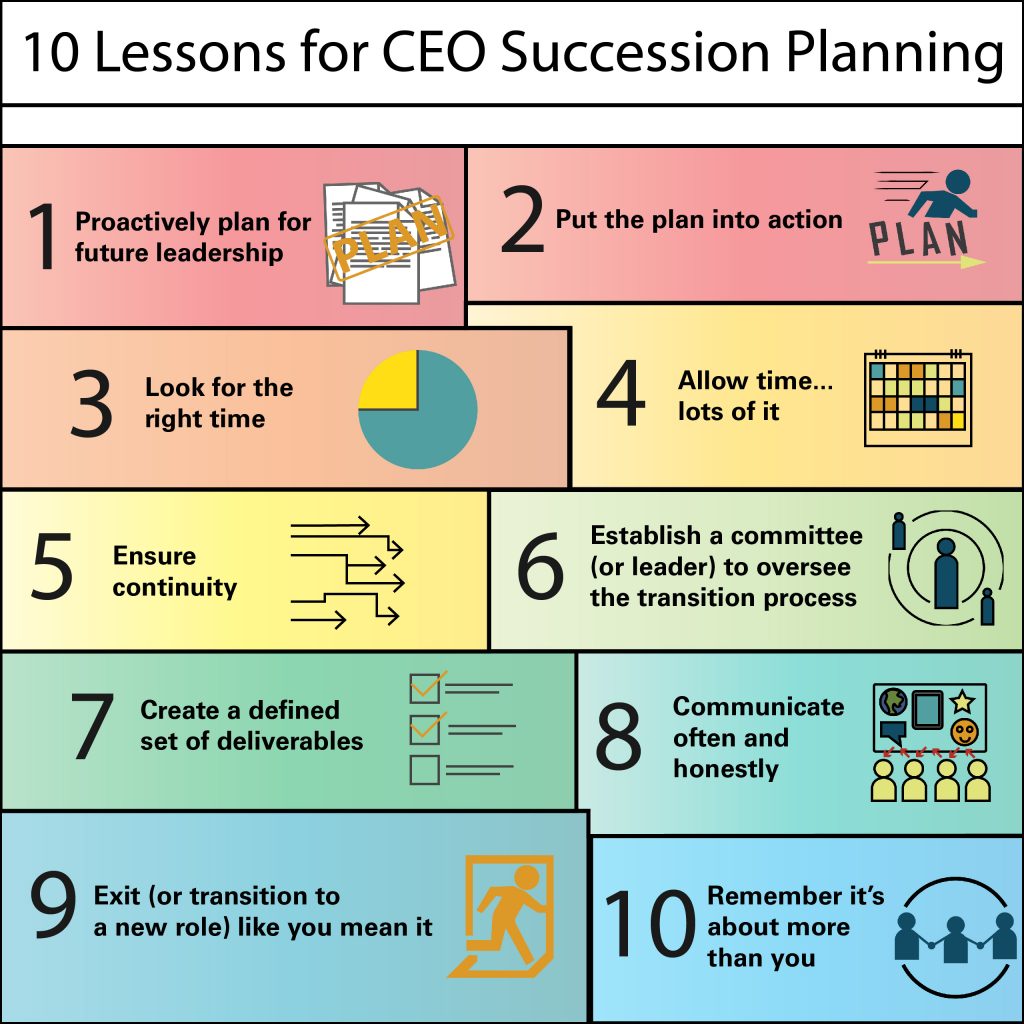

More than a decade ago, Bridgespan Group Chairman and Co-Founder Tom Tierney predicted a nonprofit leadership deficit due to sector growth and baby boomer retirements. One of the consequences of this trend is an increase in CEO successions—an often-dreaded process. It’s also a process that many organizations aren’t prepared to address. In its 2017 National Index of Nonprofit Board Practices, BoardSource found that only 27% of nonprofit boards have a written executive leadership succession plan in place. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

We can’t claim to have all the answers, but lessons from members of the Leap Ambassadors Community and other thought leaders provide some helpful guideposts for a successful, planned transition. With reflection, planning, communication, and time, a change in nonprofit leadership can be a positive experience for organizations of all sizes.

Bob Rath, who served as CEO of Our Piece of the Pie for 23 years, initiated the conversation among Leap Ambassadors by sharing his personal succession journey with refreshing honesty (see Appendix). His post triggered Ken Berger, Chip Edelsberg, Linda Johanek, Bridget Laird, Amy Morgenstern, Lou Salza, and Rick Wartzman to share their own stories and advice.

We provide a summary of their insights below. But we’ll kick off this synthesis with some words of encouragement from Laird, the current CEO of WINGS for Kids: “When I was going through the process of CEO succession, I kept hearing negative things, summed up mostly as, ‘Ugh, it was such a nightmare.’ It was the complete opposite for me.”

Succession planning is one of the most important responsibilities of a nonprofit board of any size, and it’s critical to high performance. Yet many boards still don’t prioritize this work. Morgenstern, a leader in nonprofit governance and planning, shares:

“I have encountered some boards who think that if they address succession planning they are signaling that the current CEO needs to depart, and they do not want to send the wrong message. In other cases, to circumvent prompting a top leadership change, they avoid carrying out this governance responsibility. Having a succession plan in place is an essential high-performing board practice (for the current CEO, too). Organizations should do so well before beginning to address the current CEO’s departure date.”

Succession planning isn’t a one-time exercise or a pesky compliance item to check off a to-do list. The real purpose of succession planning is to ensure the organization prepares for what leadership transitions involve and develops its internal talent pool, long before a succession occurs. A principle from the Performance Imperative’s Courageous, Adaptive Executive and Board Leadership pillar describes it best:

“Executives and boards engage in succession planning for CEO, board chair, and other senior leadership roles. They place leaders in roles to challenge and prepare them for greater responsibility.”

For example, one organization’s succession plan called for giving promising leaders additional responsibilities or special assignments—some outside their comfort zone—to assess their capacity for executive leadership roles. Long before it was time for leadership changes, the organization had insights on the capabilities of potential internal candidates.

CEOs who lead with the best intentions can struggle with the hard decision to depart an organization. As Johanek, a Leap support team member who served for nine years as CEO of the Domestic Violence and Child Advocacy Center in Cleveland, OH, affirms, “A CEO, especially a long-serving CEO, needs to be aware when the time is right to exit and make way for a new visionary.”

In 2015, Salza, then head of school of the Lawrence School, decided he would be ready to make the transition into retirement in 2018. So he reached out for guidance. He says, “I have a wonderful network of colleagues and friends across the country. There are colleagues who are a few steps ahead of me on the escalator. I always ask, ‘What was that like for you? What worked? What didn’t work? What advice might you give me?’ I go into this next phase of my life with my eyes open. And I’m not particularly worried about it.”

For others, like Rath, the decision takes more time. As he describes:

“My personal journey started 11 years ago, and my biggest barrier was denial. I didn’t believe I was ever going to need to leave. Once I broke that barrier, which took several years, I moved rather quickly through anger (I’m generally not an angry guy). Then I took some time bargaining with myself and others about how it could work, spent a little time being depressed, and then moved into acceptance.

“For me, acceptance is a clear-headed state where there’s no regret. Once I got there two years ago [2015], I initiated a conversation with our board chair, with my exit date clearly framed and an outline of a plan for how we’d get there.”

Successful transitions, from the first thought an outgoing CEO has about departing to the time when a new CEO is in place and ready to lead, can take from six months to four years or more, depending on the complexity and size of the organization.

Even with a generous six-month overlap with the outgoing CEO, Laird still wished for more time. “I wish we would have had more time navigating donor relationships. I would love to see some thought pieces on best practices for managing and handing off relationships.”

In retrospect, she believes, “The key to our success was time. This process was not done in a rush. It probably took about four years from when the discussions really began in earnest until day the founder exited.”

Rath’s transition allowed plenty of time as well. He says, “This public portion of the succession timeline began approximately nine months prior to my expected exit, including a built-in four-month cushion. Milestones in our timeline of activities for succession include announcement in January, search process commences in February, candidate interviews in April and May, offer in June, and successor at the organization in September.”

Once the succession process is underway, it’s important for organizations to try to avoid other leadership transitions (e.g., board chair) to safeguard organizational stability. As a result, an important component in Rath’s succession plan was “firming up board leadership for the period of transition.” When Laird was promoted from COO to CEO, she and the founding CEO asked the board chair to serve an additional term. Laird was initially named executive director for six months while the founding CEO remained. “I was [our outgoing CEO’s] shadow during that overlap period,” Laird says. “I went to all meetings and listened to discussions. I was able to debrief with her after each meeting and learn the ‘why’ behind her decisions. It was invaluable to me and the organization.”

Make sure everyone knows who is in charge of the process and pick the right person (or people).

Rath outlines one approach: “I asked for a small board committee with whom I could talk openly … and a trusted consultant to help navigate the entire process. This [consultant] role was critical during the 18-month private discussion period.”

A designated leadership structure to manage the transition helps alleviate staff and stakeholder anxiety. And functionally, it allows the organization to think critically about the needed skills and characteristics in the next CEO. This group should set a schedule, communication norms, and benchmarks, and manage continuously toward those ends until the transition is complete.

Establishing a detailed set of goals and deliverables for the transition period helps retain institutional knowledge and makes the most of the outgoing CEO’s time.

In an effort to pass on institutional knowledge during the final ten weeks of the transition, Johanek made a special effort to include the Interim CEO in a variety of meetings and tasks. “I was still CEO and had the decision-making authority but knew the Interim CEO would have to live with the results. So, in many of our meetings, I would say, ‘This is my opinion, but what do you want to do since you will be making these decisions on your own soon?’” she explains. “It was a great process that allowed for rich discussions. It was a letting-go process for me and an empowering process for her—an important part of the transition.”

When Edelsberg decided to step down from his role as executive director of the Jim Joseph Foundation, he used a series of meetings to achieve transition goals. “We brought [the incoming CEO] into the office on occasion…. I conferred with board members—as I did anyway—on a regularly scheduled basis about the transition. You don’t want your board members being surprised, even if it’s just a rumor. He and I met around the strategic plan items, board meeting agendas, governance documents, by-laws, employee performance reviews, etc. And, he, of his own accord and with some introductions from me, went about the process of getting himself acquainted with the CEOs of the major grantees of the Jim Joseph Foundation.”

Sometimes, significant overlap with an outgoing CEO isn’t possible. Yet even in short transitions, CTC Academy Executive Director Berger, who’s been both an incoming and departing CEO, advises, “There must be board involvement in developing a formal transition plan with action steps and metrics for leadership hand-off.”

Almost every ambassador we interviewed—and several thought pieces we reviewed—stressed the importance of ensuring confidence through clear, consistent, and honest communication with all stakeholders—from clients to staff to community partners. As Berger explains, “The more stakeholders know, understand, and see that there is a clear plan and process in place, the better an organization will weather the succession process.”

Johanek underscores the importance of having a detailed communications plan. “We spent a great deal of time discussing levels of communication and priority order regarding major donors, other funders, project partners, general community partners, staff, board, and volunteers…. We paid great attention to timing and created a schedule for reaching out to each group. My greatest fear was that the news would leak somehow, and staff would learn from someone else off the record. Fortunately, that didn’t happen, partly because of the integrity of those I told and partly because of the detailed schedule we developed.”

Johanek and team carefully developed and deployed core messaging around her transition. “It was important to provide details about my resignation, effective date, and future plans to indicate that it was my choice to leave—a positive outcome rather than being fired and having no plans,” she explains. “We included a quote from the board chair about the board’s confidence in the agency’s succession plan. We provided details about the interim CEO’s credentials and experience to explain clearly who was in charge. And finally, we ended with a positive message about the agency’s ability to continue to thrive.”

Salza knows the importance of early and often communication. In fact, he made his retirement official with a letter notifying the board 18 months in advance. But before making it public, he met with the school faculty. “Of course, because it was so far in the future, people thought I was leaving at the end of June 2017. ‘No, I’ll be here for the whole 2017-2018 school year,’” he clarified. “I think that helped to allay some feelings. And, of course, kids are amazing. I was at the lower school not long ago, and a third grader in the art class looked up and said, ‘Are you overtired yet?’ I’m still thinking of an answer!”

Some believe that it’s best for a CEO to make a clean break from the organization. Staying on in some capacity has been described as having a “ghost in the attic.” Rath agrees. “It’s about exiting. Not tethering. Some might be tempted not to exit entirely [and] instead to find an ongoing role. This is not an exit.”

Laird’s experience embodies this “clean break” philosophy. After a lengthy transition period, the outgoing CEO insisted on a 45-day moratorium on all communication with her. Though difficult, “This break helped me really come fully into the leadership role and learn to trust my own decision-making. The outgoing CEO also dropped off the board for three years. This was critical in preventing them from having a built-in person to judge me against and second-guess my leadership.”

In some cases, however, ongoing ties between the outgoing CEO and the organization are healthy and innovative.

As founding executive director of the Drucker Institute, Wartzman hired a COO he admired and respected. Regular check-ins about the COO’s development as a leader were a norm. Over the course of these conversations, he realized that the COO was ready to run something on his own. Wartzman was also ready for a new professional challenge.

Wartzman, with the encouragement of a supportive board, stepped down as executive director and became director of a Drucker Institute initiative. Upon reflection, he thinks one of the most important reasons this transition succeeded was because of the clearly defined new role. As he puts it, “My new position wasn’t a ‘pity’ role. I had clear, important things to work on, which was key to our success. Defined work and objectives were critical, allowing me to advance strategic projects.”

As Dawne Bear Novicoff, COO of the Jim Joseph Foundation, wrote in the Adidas & Ascots: Effective Leadership Comes in Many Styles blog post, “A successful transition is not only about the two individuals but about the readiness of the team to rise to the occasion and support the leadership change.”

Helping staff navigate the often-murky waters of a leadership transition can be difficult. “Change is not easy, and staff tend to wonder how the change will impact them and their role at the agency,” Johanek says. “I heard from staff who were afraid that we would change from a victim-advocacy organization to a mental health organization and other fears…. Helping staff to manage change and manage fears is critical. Beyond acknowledging fears and having a healthy dialogue, we received a grant for change management funds as part of our succession plan to support staff, board, and agency operations. For example, we planned to use funds for a facilitator to lead staff group dialogues around transition issues.”

Edelsberg set office hours for staff to ask questions about current projects or other work-related items and established “coffee hours” to discuss questions and concerns about an employee’s future or career path. These coffee hours, conducted outside the office and work hours, established a clear break between his counsel as boss and his guidance as a mentor and empathetic leader.

Salza and his team made the transition a learning process for the entire staff and an opportunity for them to help develop leaders beyond self and school. He says, “I think retirement is kind of about you, but it’s not all about you. I think it’s mostly about the organization. And it’s mostly about people focusing on what the imperatives for the school will be going forward. You don’t let the cult of a personality or the shadow that’s cast by a strong leader get in the way of people seeing that clearly. I think that’s the dance you have to do. You have to be willing to accept the responsibility you have for what’s going on right now and be as gracious and accommodating as you can be.”

Succession planning is often associated with feelings of angst, fear, and sometimes even outright panic. Berger summed it up best: “Generally, succession planning has more of a duck-and-cover tendency rather than a proactive, positive approach. Nonprofits need to develop a culture of succession thinking from the top to the bottom of the organization.”

Interested in more learning more? Here are five references to consider:

Special thanks to Leap Ambassadors Ken Berger, Chip Edelsberg, Bridget Laird, Amy Morgenstern, Bob Rath, Lou Salza, and Rick Wartzman, who shared their stories; Donna Stark, from the Annie E. Casey Foundation who provided curated references on the topic; Dawne Bear Novicoff from the Jim Joseph Foundation for the blog post; and Linda Johanek from the Leap Ambassadors support team.

The Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community is a private community of nonprofit thought leaders, leader practitioners, forward-looking funders, policy makers, and instigators who believe that mission and performance are inextricably linked. The community’s audacious purpose is to inspire, support, and convince nonprofit and public-sector leaders (and their stakeholders) to build great organizations for greater societal impact, and increase the expectation and adoption of high performance as the path toward that end.

Editor’s Note: Bob Rath, CEO of Our Piece of the Pie® since May 1994, publicly announced his retirement plans in 2017. Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at how he and his board prepared.

Succession planners and consultants suggest that CEOs planning to leave their organizations allow six to nine months to plan the announcement. In my experience, this just isn’t enough time.

The reality is that retiring and leaving an organization to which you are deeply and personally committed resembles stages similar Kubler-Ross descriptions of death and dying. (I’m not kidding.) Expect to journey through denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

This takes time. But first, a few rules for the road:

My personal journey started 11 years ago, and my biggest barrier was denial. I didn’t believe I was ever going to need to leave. Once I broke that barrier, which took several years, I moved rather quickly through anger (I’m generally not an angry guy). Then I took some time bargaining with myself and others about how it could work, spent a little time being depressed, and then moved into acceptance.

For me, acceptance is a clear-headed state where there’s no regret. Once I got there two years ago, I initiated a conversation with our Board Chair, with my exit date clearly framed and an outline of a plan for how we’d get there.

The components of the plan included:

The end of the private discussion period began with my announcement of pending retirement to the full Board during an executive session. And immediately following, the Board Chair outlined the plan of activities.

A month later, I informed my direct reports with an admonition to keep the information private and outlined the plan of activities. Another month later, as scheduled, the Board Chair and I met with all staff in a day-long road show at organization work locations.

Simultaneously, select Board members called key individuals, and I distributed the official press and social media releases. This public portion of the succession timeline began approximately nine months prior to my expected exit, including a built-in four-month cushion.

Milestones in our timeline of activities for succession include announcement in January, search process commences in February, candidate interviews in April and May, offer in June, and successor at the organization in September. If a CEO cannot be found within the timeline, the Board will hire an Interim CEO.

The overall plan has stood up to some unexpected glitches, and, though it is not complete, it is moving forward essentially on schedule. One new feature we’ve added along the way is a role we have labeled the “Transition Executive,” which we have assigned to our CFO, who participates in key decision-making activities to strengthen organizational continuity.

Orchestration is a core function of the CEO that must be performed up to, and including, my exit.

Mission (soon) accomplished.

Bob Rath, CEO of Our Piece of the Pie® since May 1994, publicly announced his retirement plans in 2017. Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at how he and his board prepared.

This document, developed collaboratively by the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community (LAC), is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. We encourage and grant permission for the distribution and reproduction of copies of this material in its entirety (with original attribution). Please refer to the Creative Commons link for license terms for unmodified use of LAC documents.

Because we recognize, however that certain situations call for modified uses (adaptations or derivatives), we offer permissions beyond the scope of this license (the “CC Plus Permissions”). The CC Plus Permissions are defined as follows:

You may adapt or make derivatives (e.g., remixes, excerpts, or translations) of this document, so long as they do not, in the reasonable discretion of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, alter or misconstrue the document’s meaning or intent. The adapted or derivative work is to be licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, conveyed at no cost (or the cost of reproduction,) and used in a manner consistent with the purpose of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, with the integrity and quality of the original material to be maintained, and its use to not adversely reflect on the reputation of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community.

Attribution is to be in the following formats:

“From ‘Graceful Exit: Succession Planning for High-Performing CEOs,’ developed collaboratively by the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, licensed under CC BY ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/“

The above is consistent with Creative Commons License restrictions that require “appropriate credit” be required and the “name of the creator and attribution parties, a copyright notice, a license notice, a disclaimer notice and a link to the original material” be included.

The Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community may revoke the additional permissions described above at any time. For questions about copyright issues or special requests for use beyond the scope of this license, please email us at info@leapambassadors.org.

We use cookies for a number of reasons, such as keeping our site reliable and secure, personalising content and providing social media features and to analyse how our site is used.

Accept & Continue